Openings

Contents |

15th Century

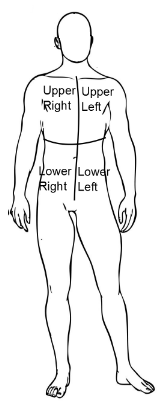

The early Germanic fencing tradition held to a system of only 4 openings, dividing the opponent into quadrants around their 'girdle'. The diagram below shows an approximation of this schema.

Notice that the openings are specified from the point of view of the target's frame of reference, so the upper left opening referred to the target's upper left, rather than the upper left from the point of view of the attacker.

The openings have great relevance to the Tactical Approach of the early Liechtenauer system.

16th Century

4 Openings (high/low)

The four openings are a common part to most of the German fencing tradition. In essence there are four main openings based on a division of the target into quadrants.

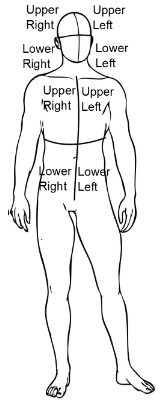

Meyer uses the standard division of the target into these quadrants throughout his text, though augments it by further dividing the target as needed into quadrants for particular target regions. Whereas earlier masters divided the body into a simple four quarters (upper left, upper right, lower left, lower right) Meyer also divides the head into four quarters so that we can strike to the lower left opening of the head, or the upper right of the head. He does also use a more generic four openings in his Dussack section; in this case the centrepoint for the four openings is around neck level for the target. The remaining sections on rappier, dagger, and polearms, use the same openings as the longsword and dussack sections.

One can speculate that this represents a focus on blows to the head in 16th century fechtschulen as a means of “scoring”, though it may simply be a natural extension of older terminology to provide more accuracy/precision in practice.

Notice that the openings are specified from the point of view of the target's frame of reference, so the upper left opening referred to the target's upper left, rather than the upper left from the point of view of the attacker.

Attacking the Four Openings in the Onset

In his section on the Meyer Square (more accurately his section on how one should attack the four openings) Meyer briefly describes general principles for attacking the openings. He favours attacking on opposite diagonals in the onset. So for example if the fencer attacks to the upper left opening initially, then they should immediately strike to the lower right opening afterward as a general principle (depending on the circumstance of course).

The rationale here is that the opponent has had to go up again this high blow so will have left the lower opening unguarded in doing so.

From here Meyer changes off to the opposite side on the same level (so in our example he would follow with a cut to the lower left), then again to the opposite diagonal at the newly created opening (the upper right in this case).

So as a general rule attacking the openings is carried out as follows:

- Attack an opening

- Attack the opening on the opposite diagonal to the previous strike

- Attack the other side on the same level as the previous strike

- Attack the opening on the opposite diagonal to the previous strike

This is demonstrated in the Attacking to the Openings Device 127v.1.

Further advice on attacking in the onset is given in the dussack section.

We are told to look for moments where the opponent's weapon is held too high or low, or too far out to the side. In finding our opponent exposed this way we are to cut quickly in to the opening, and just as it hits to cut quickly back opposite it (which could be horizontally or diagonally opposite, from the initial cutting sequences).

In this we are told to beware of opponents who offer such openings as a way of luring us in, for if we do so he can at once step out and overreach you with a cut at the same time.

With this in mind we should be ready to pull our initial cut and use it not as a direct attack, but as a way of luring our opponent out of their guard position toward the opening we're attacking, so that we can immediately strike to the opposite opening they just vacated. Meyer calls this kind of strike a Provoker.

Attacking the Opponent's Openings after they Cut (or Parry)

Just as we can attack the openings in the onset, Meyer also points out that we should follow similar principles when chasing an opponent after an attack (Nachreisen). This should follow the general rule of opposite diagonals as seen before, however in this case the fencer is attacking the opposite diagonal to the opening in which the opponent's blade ends its motion.

For example, if the opposing fencer cuts a Zornhauw from his upper right all the way through to wechsel on the left they end with their sword in the lower left quadrant. We should immediately then attack the upper right opening in response as this is at the furthest extend from the opponent's sword, and requires a complete change of direction of their blade in order to parry. This is further emphasised in the dussack section wherein it is stated that:

"He is most open in the part from which he sends in his stroke. This is a very noteworthy precept, which you shall study diligently and to which you shall give attention..."

Of course, these are general rules and as the devices teach us they are used judiciously at the correct moment, rather than adhered to dogmatically.

Rappier

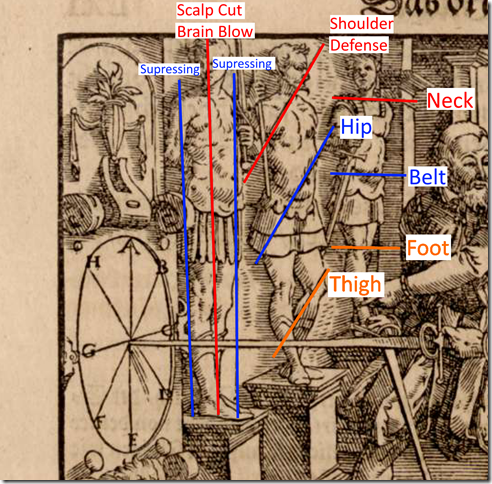

Meyer's rappier section defines a more complex series of openings along multiple lines of the body. These are annotated below:

This image was used from the Grauenwolf blog.