Gripping the Longsword

It seems obvious that in order to use a longsword you must first learn to hold it properly, yet often little thought is given to the many ways of gripping a longsword and the difference it makes to the execution of a cut or other technique.

First then, some general advice for gripping the sword:

Generally a longsword is not held in the lead hand with a tight perpendicular grip (the kind of grip you would use to swing a hammer). This kind of grip causes stiff movements and poor edge control through a cut, and doesn't allow us to use the point well. Instead grip most strongly with the last three fingers of the hand, with the index finger and thumb not gripping tightly at all this grip is slightly angled so that the wrist does not fall perpendicular to the grip, but instead allows a natural extension of the arm. Keep the grip supple; choking the haft leads to stiff and clumsy techniques. Usually the grip is fairly soft until the moment of impact, at which point it becomes tighter and more secure.

If your wrist is bent at a sharp angle during a particular guard or cut, then chances are you’re doing it wrong. Generally the structure of the wrist and hand should be aligned without excessive flexion or extension of the wrist. Sharp wrist angles weaken one’s grip on the sword and afford opportunities for the opponent to use wrist locking movements.

Taking these points into account, we can now identify specific gripping methods to which we might apply them.

Contents |

The Orthodox Grip

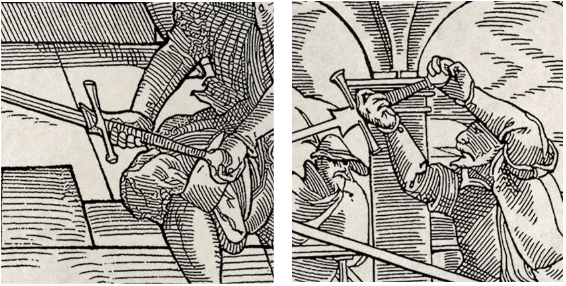

The leftmost plate in the series depicts what we would generally describe as the orthodox grip for the longsword. In this grip the lead hand is close to the crossguard, with the thumb just touching/overlapping the guard slightly.

The rear hand can either grip the pommel, or hold the grip just above the pommel itself. Which particular grip you use depends on your personal style and preference. However gripping the pommel usually permits easier winding and levering movements of the blade, while gripping the haft above the pommel seems to improve cutting alignment in larger cuts; indeed the rear hand will often be used to move the sword around by adjusting it's position, and so the fencer should not clench too tightly in one position, but rather be ready to move into a new position quickly.

As an example of this, Dobringer, the 15th century fencing master, advocates the use of the grip above the pommel for strong cuts, suggesting it makes cuts faster by creating a balanced pendulum action saying “And you will also strike harder and truer, with the pommel swinging itself and turning in the strike you will strike harder than if you were holding the pommel. When you pull the pommel in the strike you will not come as perfect or as strongly.”

Whether or not this is borne out by the evidence is questionable, however it does give an example of moving the hands to a new position to achieve different kinds of striking.

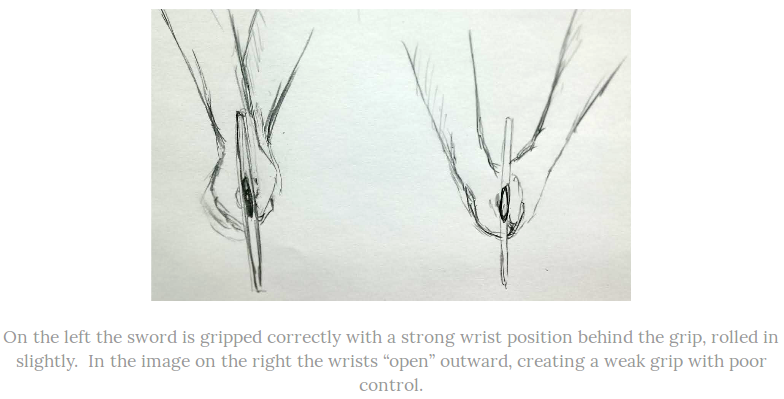

The cutting motion for major cuts with the orthodox grip should use a levering action. The lead hand becomes a moving fulcrum for our lever and the rear hand imparts the force by drawing the pommel in opposition to the lead hand. This means that the rear hand is really doing all of the work of turning the blade, while the lead hand casts forward and creates a solid centre of rotation for our cut. While cutting the wrists should be rolled inward so that they’re pushing it from behind; this prevents the wrists from bending on impact and avoids losing control of the sword. It also helps keep correct alignment of the blade.

Throughout the acceleration phase of the cut the grip should be supple on the hilt, if cutting through the target the grip will firm at the point of impact, while if cutting “to the point” (that is to say halting the blade with the point in line with the target), there will be a notable tightening which almost “snaps” into position to lock the grip and arrest the motion of the blade.

The Thumbed Grip

The thumbed grip is seen more often in German longsword techniques than in other longsword arts. Most often it is used for cuts which use rotation involved in crossing or uncrossing the arms. These are largely known as “crooked cuts” because they allow angles of attack which are off centre or not in line with the basic cutting lines.

In the thumbed grip the front hand holds the blade with the fingers while the thumb itself is pressed against the forte of the blade to create a rigid rotational structure. The thumb should usually be facing inward toward the sword wielder, rather than outward at odd angles, during a thumbed cut or block.

The rear hand in the thumbed grip is most often seen on the pommel, though this is just a general guideline and a haft grip can be used if preferred.

The Ball & Socket Grip

This unusual seeming grip is seen in Meyer in situations requiring the pommel of the sword to be moved around with maximum freedom. In this grip the lead hand is in the orthodox position, but the rear hand is held over the pommel forming a kind of ball-and-socket joint which allows unmatched dexterity in manipulating the pommel. This grip is seen in techniques which rely on winding or manoeuvring the blade using the pommel. It provides a fairly poor structure for normal cuts, but for winding and pivoting movements it is an excellent alternative to the orthodox position.

Crossed Hands Grip

The crossed hands grip is essentially the orthodox or thumbed grip just performed with the wrists crossed. When at the extremes of motion the crossed hands grip may require the pommel to be held quite loosely with the rear hand in order to maintain good wrist structure. The crossed hand position is often seen with on-point guards on the right side of the body such as pflug and ochs.