Cutting Mechanics

There are two distinct approaches to cutting in the texts, cutting through and cutting to the point.

Contents |

Cutting Through

Cutting through refers to taking the blade all of the way through the target and to the other side. An Oberhau for example might cut all the way through a target and fall down into an Alber type of position.

The mechanics for cutting through typically engage the larger muscle groups as a part of the cutting process, and rely less on a "push-pull" of the grip, and more on a swinging of the whole body as a single motion segment.

We see this kind of cut in the section on over-running (Oberlauffen), in which the opponent cuts too far, allowing the opponent to chase after their cut to the upper opening.

For this very reason the 15th Century writers admonish us not to make too much use of these wider cutting movements, instead cutting to the point.

Cutting to the Point

Cutting to the point refers to ending our cuts with our point very much toward the opponent, rather than cutting all of the way through the target and (for example) to the ground.

The mechanics for cutting to the point rely on more of a push-pull action of the hands which accelerates the blade quickly in a tight circle. Because we need to end on-point our cuts rarely travel far past the impact point. In the case where the opponent voids our attack this means we must also rapidly decelerate our cuts (though if they are hit or parry then their body or blade does that work for us).

Cutting to the point is seen as a superior method in the early texts as we end with our blade in a position to thrust or to set aside the opponent's attacks, though the cuts rarely land with as much force as a full cut through.

Comparison of 15th vs 16th Century Longsword Mechanics

The Liechtenauer glosses are quite clear that right handers should predominantly open with cuts from the right side, left handers from the left, as these are their dominant side. Both texts advise fencing with the whole strength of the body, which is not to say hit as hard as you can, but use your whole body movement for your cutting.

Hand Position in High Cuts

Cuts such as the Oberhauw in the 15th century are often taught with a lower hand position in relation to point through the cut. This somewhat more "retracted" hand position helps avoid hits to the hand and provides better leverage in the bind.

By comparison the 16th century sources seem to favour an extended arm position and the text specifically tells us to use the full extended position quite often, as we see below:

At first this might be seen to expose the hands to more risk, however the style of fencing done in competition during Meyer's time seems much more "blade" oriented and less resolute on entering.

Another explanation is that actual longswords at this time generally possessed side rings which provide safety in these kind of binds.

Hip Turning & Contrapposto Movements

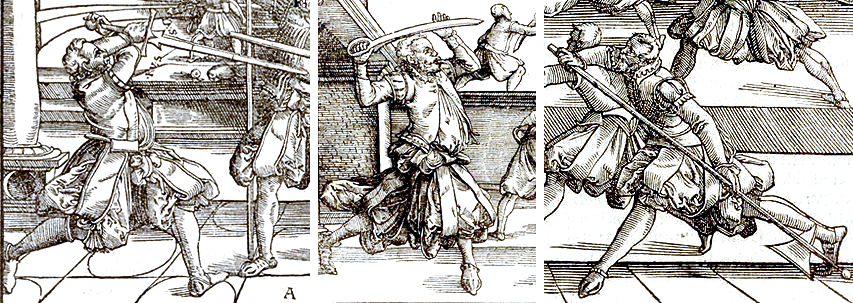

Arguably both 15th and 16th century arts rely on a turning of the hips prior to stepping as we perform cuts, resulting in a contrapposto body position with the lead leg turned slightly out. This is especially visible in Meyer's system:

This position can be used at the beginning of a cut, or even as we transition from one guard to another. For example we can move from a Pflug on the left into a Pflug on the right first by moving the blade across and adopting an contrapposto position, then stepping forward with the left leg to complete the movement.

For both cuts and blade transitions this type of movement allows us to cover our line safely with the blade prior to committing to the cut.

Whether this is seen in 15th century systems is debatable.